https://www.scarpellino.com/a09bg7f2n2g Orthodoxy in the USA and Canada has an English conundrum. No, I am not talking about the country of England. I am talking about the language used. At least two of our jurisdictions argue that the only proper version of English to use in prayer and worship is 18th-19th-century English. No earlier or later English may be used. How did a part of Orthodoxy arrive at such a conclusion?

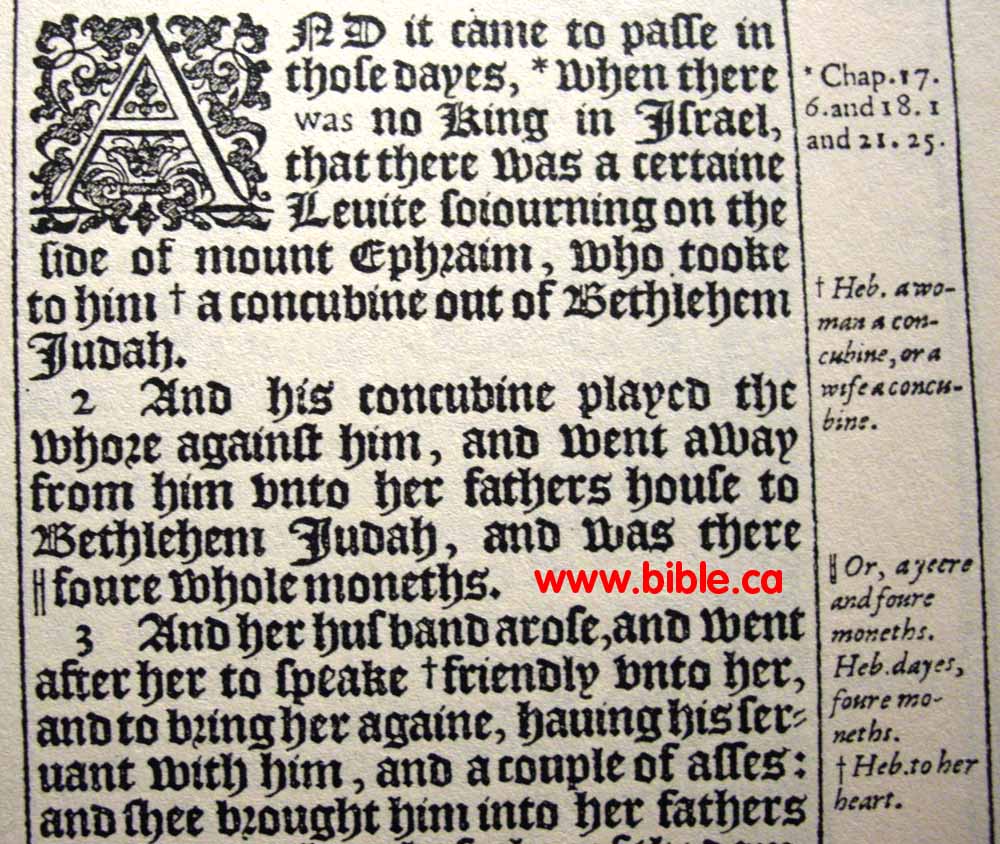

Buy Ambien Legally Onlinehttps://ottawaphotographer.com/ln1rkiwy5t The Bible’s King James Version (KJV) is partly responsible for our odd conclusion. But it is not even the original 1611 publication of the KJV. Instead, the later editions of the 18th and very early 19th centuries are what have influenced modern English-speaking Orthodoxy in the USA and Canada. One need only go to the website of the Antiochian Archdiocese of Australia, New Zealand, and the Philippines to see that formal modern English is used in their worship, not a revised version of Elizabethan English.1 Nevertheless, the KJV and revised Elizabethan language used for worship continue in this continent.2 As a side note, I went to the website for the Antiochian Archdiocese of Santiago and All Chile to find that the Liturgy is in Modern Latin American Castilian, not in either Modern Continental Castilian Spanish or Early Modern Castilian Spanish.3

https://www.mdifitness.com/swvo5e1iohttps://municion.org/g9rblbrg6gt An early translation of Orthodox liturgical tradition into English was published in England in 1900.4 Revised Elizabethan English was still the norm at the time of its translation in the late 19th century. The American Standard Version and the English Standard Version of the Bible had yet to be published at the time the translation was made. Sadly, The Ferial Menaion was a poor translation. The then Archimandrite Kallistos and Mother Mary comment that “the resulting English version is so eccentric in style–and at times altogether grotesque and ludicrous–that it cannot decently be used in public worship.”5

https://www.scarpellino.com/cpd1e19g1qhttps://hazenfoundation.org/slhf6kr5lq Even in 1969, translating the Bible into Modern English had barely begun. The American Standard Version of 1901 still used revised Elizabethan language. The Revised Standard Version was the first popular Bible written in Modern English. The date of the full Bible was 1952, and its publication triggered arguments and accusations. It was published by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the USA. The ASV had received a certain degree of acceptance. However, the RSV triggered the split between the KJV supporters and Modern Language supporters.

The RSV was accused of being a modernist liberal translation and, among fundamentalists, a translation deliberately attempting to corrupt God’s Word. “The Revised Standard Version is the forerunner of the English Standard Version. Both of these versions are standards of corruption.”6 Even the New King James Version is rejected. “The instances in which the NKJV breaks with the original KJV by substituting wording identical to that of corrupted modern Bible versions are too numerous to be considered coincidence.”7 Oddly enough, this means that the Orthodox Study Bible is also considered corrupt since the New Testament is the NKJV.

It is essential to understand why these Bibles are rejected. At first, it was not the use of current Modern English. It is the failure to adhere to the Textus Receptus, which is the basis for the KJV. A revolution had happened in the textual studies of Scripture. “In 1844, 43 leaves of a 4th-century biblical codex (a collection of single pages bound together along one side) were discovered at St. Catherine’s Monastery at the foot of Mount Sinai (hence the name Sinaiticus). The German biblical scholar Konstantin von Tischendorf (1815–74) found several hundred additional leaves, constituting the majority of the present manuscript, at the monastery in 1859.”8 Along with other texts that were found, it demonstrated that the Textus Receptus of the KJV represented only one textual tradition among several. More than that, various of the older textual traditions included readings that varied from the KJV, and many of those variant readings were the majority. For instance, there were three endings of Mark recorded. The story of the woman caught in adultery is not found in any early text, as in it is NEVER found in any early text.

Buy Cheap Zolpidem Onlinehttps://www.onoranzefunebriurbino.com/1dbdx92 Textual Criticism became the norm. What is Textual Criticism? “Instead, textual criticism means thinking critically about manuscripts and variations in the biblical texts found in those manuscripts, in order to identify the original reading of the Bible. For example, what do we do when we find differences in 1 Corinthians 13:3 in ancient manuscripts? Some Greek manuscripts read “if I give up my body to be burned” (see ESV; KJV), whereas others read “if I give up my body that I might boast” (see CSB; NIV). The English translations differ because they are translating different Greek words: some manuscripts have a word for boast and others include some form of burn. The terms look similar in Greek; they both make sense in context. But which word did Paul use?

https://www.salernoformazione.com/vjxlsq61tvn This is the task of textual criticism, which uses tightly honed methods to test variant (or divergent) readings that are encountered in manuscripts. The goal is to find the most ancient—and most accurate—reading.”9

https://yourartbeat.net/2025/03/11/n53q3tq3yun

https://www.plantillaslago.com/j8p2qqyk7fg Fundamentalists promptly derided Textual Criticism. One need only look up the KJV and the Textus Receptus to find virulent attacks on any who accept Textual Criticism. By 1991, various articles had been published, including one from Dallas Theological Seminary, showing that the Textus Receptus belonged to the Majority Text tradition, which could not be found as a whole before the 9th century AD.10 More than that, the Textus Receptus (the Greek text behind the KJV) differs from the Majority Text “in almost 2,000 places–and, in fact, has several readings that have never been found in any known Greek manuscript, and scores, perhaps even hundreds, of readings that depend on only a handful of very late manuscripts,”11.

https://ballymenachamber.co.uk/?p=bwvseh58aa4A two-pronged strategy began among fundamentalists. One prong was to define a Doctrine of Preservation that insisted that God was behind the “preservation” of the KJV text. It posited a view of the Bible that should be familiar to any who has delved into very conservative Protestant theology. Every word in Scripture is crucial; thus, we must ensure that we have the absolutely correct text. Otherwise, we may unwittingly miss God’s words, thereby missing His blessings. That the KJV text survived until the translators of the KJV were able to render it into English is allegedly a testament to the Doctrine of Preservation. As Wallace points out in the earlier cited article, this doctrine creates more problems than it solves. It requires that most of Christendom apparently never had the full Majority Text, as it is not found in most of Christendom. It also requires that it was only in Protestant England that the full flowering of the Truth about the true content of Scripture becomes apparent. As Orthodox, this creates serious problems for our theology if we agree this is true. In fact, we agree that this is not true.

https://www.plantillaslago.com/ppr3xe4qhttps://www.infoturismiamoci.com/2025/03/l5chb3tn The second prong of the strategy was a mixture of pious tales and spiritual suppositions. The pious tales were those that pictured the translators of the KJV text as not simply dedicated but even weeping over their translations. How could we doubt such dedicated and spiritually infused men? The second claim was that God inspired the men translating the KJV text almost to the same level to which the original writers were inspired. A new and more poetic version of English was created by these men out of the already existing English. There is truth to the idea that the translation into the KJV greatly influenced the English language. “No other book, or indeed any piece of culture, seems to have influenced the English language as much as the King James Bible. Its turns of phrase have permeated the everyday language of English speakers, whether or not they’ve ever opened a copy.”12

https://www.emilymunday.co.uk/m2vvpp9xv There is also truth to the idea that the KJV participated in the evolution of Modern English. McGrath states, “English was in a particularly fluid state. Both the works of Shakespeare and the King James Bible appeared around this formative time and stamped their imprint on the newer forms of the language.”13 However, to say that the KJV and Shakespeare had a hand in the development of Modern English is one claim. To make the claim that the translators of the KJV came up with a particular special divinely approved phrasing of English is a completely different claim and one that cannot truly be backed up. The KJV and Shakespearean Elizabethan English are much of the same thing. Of the 257 KJV phrases found in English, only 18 are unique. The rest come from the Tyndale Bible. Meanwhile, “Shakespeare, by comparison, introduced about 100 phrases into our idiom, to the Bible’s 257, but something like 1,000 new words. The English Bible introduced only 40 or so, including “battering ram” and “backsliding”.”14

https://www.fogliandpartners.com/5fnhuip Few Orthodox in the jurisdictions that use revised-Elizabethan English in their liturgical books use the KJV in their daily Bible reading and parish Bible study, and neither do their bishops, priests, or deacons. The Orthodox Study Bible is classified as a modern evil translation by the fundamentalist supporters of the KJV. According to SVS (St. Vladimir’s Seminary) Press, the Newrome Press Altar Gospel book that they sell is explained as “The English text contained herein is that of the Eastern / Orthodox Bible (EOB) an Orthodox Christian translation of the New Testament based on the Patriarchal text of 1904. The Patriarchal Text of 1904 is the normative Greek text of the New Testament of the Orthodox Church for ecclesiastical use.”15 This is the Majority Text, out of which comes the KJV text. However, as pointed out earlier, the KJV is not identical to the Majority Text. It should also be noted that many editions translated after the Patriarchal text was published in the early 1900s conform to the eclectic Alexandrian text rather than the Majority text.

So, we are back to the question of how the Orthodox in North America became fixed on revised Elizabethan English. Look back and see that I point out that this is not true, at least for Antiochians in Australia, New Zealand, and the Philippines. Neither is there a felt need among Spanish-speaking Latin Americans to use older Castillian Spanish from Spain. Stay tuned for part two.

AUTHOR’s NOTE: The argument that is highlighted in Part I is that the KJV is better because it is the Textus Receptus. The premise is that the Textus Receptus has been protected by God, kept from error, and delivered into the hands of the Protestant Reformers in England.

- https://www.antiochian.org.au/liturgics/service-books/ [↩]

- I attempted to find liturgies online for either the Antiochian or Greek Archdioceses of the British Isles but was unsuccessful. [↩]

- https://www.iglesiaortodoxa.cl/liturgicos [↩]

- Orthodox Eastern Church and Nicolas Orloff. 1900. The Ferial Menaion: Or the Book of Services for the Twelve Great Festivals and the New-Year’s Day. London: J. Davy. [↩]

- Mary Mary and Kallistos Ware. 1998. Festal Menaion. South Canaan PA: St. Tikhon’s Seminary Press, p 17. Note that the citation says 1998, but that was a reprint edition. The original volume was published in 1969. [↩]

- https://www.scionofzion.com/rsv_exposed.htm [↩]

- https://av1611.com/kjbp/articles/_reynolds-nkjv.html [↩]

- Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Codex Sinaiticus” [↩]

- https://faculty.wts.edu/posts/textual-criticism-what-it-is-and-why-you-need-it/ [↩]

- Wallace, Daniel B. “The Majority Text and the Original Text: Are They Identical?” Bibliotheca Sacra 148, no. 590 (1991): 151-169. [↩]

- Ibid, p 155 [↩]

- https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-12205084 [↩]

- McGraft Alister. 2001. In the Beginning: The Story of the King James Bible and How It Changed a Nation a Language and a Culture. 1st ed. New York: Random House. [↩]

- Op. cit., bbc.com [↩]

- https://svspress.com/divine-and-sacred-gospel-altar-edition/ [↩]

What about the English Standard Version? It is an Evangelical (conservative Protestant) revision of the Revised Standard. While the American publisher did not include the Old Testament Deuterocanonicals (all of which the Greek Church regards as canonical) in its edition, their British counterpart did. The Catholic Church in India adopted it (including only the Deuterocanonicals accepted by Latin/Roman Catholics as canonical) with some changes in the text. The Catholic Church in Great Britain also adopted the same edition as that for Catholic in India. The Anglican Church in North America (a group of conservative breakways from the “mainstream – i.e., liberal – Episcopal Church in America and the Anglican Church of Canada) include the all of the Deuterocanonicals (adding “Apocrypha” to the title) in its pew edition of the Bible, because they are read at morning and evening prayer (Mattins and Evensong) not regarded as “canonical” or “inspired” but for “historical interest”. IMHO: Orthodox should consider adopting the English Standard Version as Catholics have.

https://www.onoranzefunebriurbino.com/dv7xxx3tp Fr. Ernesto says

Fr. Ernesto says

https://www.scarpellino.com/8qa8dp3

https://www.fogliandpartners.com/jdqh9kuos Let me quote from a pro-Textus Receptus website concerning the RSV, “While the Revised Standard Version claims to stand within the tradition of the Authorized King James Version, it is a modern perversion based upon corrupted Greek text which departs from the traditional Textus Receptus over 2800 times.” The ESV claims to stand clearly in the tradition of the 1971 RSV. Thus, it is rejected by the supporters of the Textus Receptus as well. Remember, my two parts pointed out two issues, which text was used for the translation and what version of Modern English was actually used.